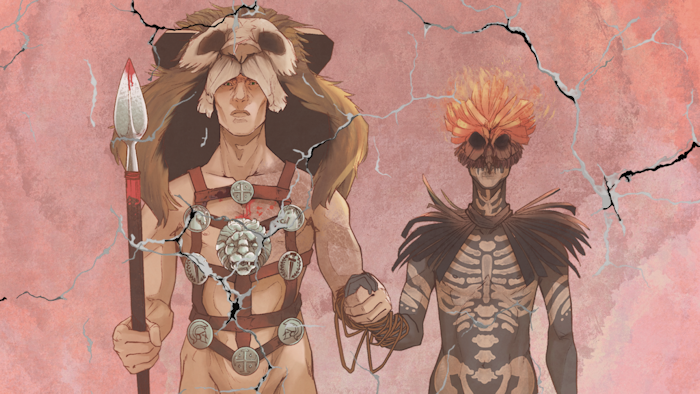

[2023- Ongoing] Serial Fiction: The Lion & The Owl – Roman and Druid lock eyes in battle, setting off a turbulent flirtation involving revenge, death, and the theft of a beloved horse.

Lucius ‘Skipio’ Servius fights in the tumultuous Gallic Wars as one of Caesar’s most trusted Legio X Equestris. His courage in battle is matched by a chivalrous respect for women—a carefully crafted facade hiding a turbulent nature. A noble man-lover, ‘Lord Skipio’ quietly wrestles with violent desires and a longing for a companion who will accept him without judgment.

Across the channel, cunning druid Aedan the Ancalite steps into his dead father’s role as a warrior, eagerly awaiting the Roman advance after drug-fueled visions foretell a fierce lover in the shape of a lion. When no man proves brutal enough to challenge him for his affections, the frustrated ‘Owl King’ wreaks bloody havoc against Caesar’s advancing legions.

[READ FREE AT BHS]

[Syndicated at Tapas, AO3.gay, and Scribble Hub.]

PREVIEW

I: The Lion

His name is Scipio Servius Lucius, or Skipio to those who call him a friend. He stands taller than most, with a powerful build, a sharply carved face, and a compelling mouth that no man resists. His shorn head gleams like ripe wheat, while his dark, moss-green eyes run deep.

Vitus Servius, Skipio’s father, is bald like his son. A burly patrician, he owns a profitable apple and pear orchard and a thriving walnut grove near the Alps. His only son eagerly trades farm life for the sword, and Vitus allows it, as he too serves Rome under the command of his oldest friend, Gaius Julius Caesar.

Skipio joins the cavalry and crosses the Alps for his first battle. Many of his boyhood friends, wealthy sons from the Larius lake region, join him, eager to prove themselves after four quiet years at the Belacius garrison. The excitement of impending battle turns to confusion when the invading Helvetii horde reveals itself as a throng of frightened migrants. Still, the call to attack comes, and the cavalry finds themselves clashing with swordless men and angry women protecting their children.

Victory leaves them hollow, their initial eagerness transforming into unease and disillusionment on the westward march.

Weeks become a month.

Skipio welters in melancholy until he offered redemption and a renewed sense of purpose by Publius Licinius Crassus.

A man of Skipio’s years and temperament, Crassus takes on a mission from Imperator Caesar to the Armorica region. Crassus rallies the Alpine cohorts, bringing them into his legion as they ride to overcome the coastal Gauls. During their time in Armorica, Crassus teaches by example, demonstrating effective leadership during the hostage negotiations with the Armoricans. Unfortunately, his approach—treating them as equals—does not please Imperator Caesar, who intervenes decisively to resolve the situation.

Skipio, determined to restore his honor and earn Minerva’s favor, follows Crassus into battle and participates in the siege of many Sotiatian cities in Aquitania. Titus joins Skipio, driven to distinguish himself through brave deeds, while Planus resolves to capture the attention of his mother’s cousin, Caesar. As the campaign concludes, Crassus reunites with the legions and returns Skipio to his father in Hispania.

Skipio, Titus, and Planus secure a place in Caesar’s new Legio X Equestris, yet elevation to the rank of decurio cannot keep Skipio from action. Never one to watch from the flanks, he rides in with his turma of thirty-two, wielding his gladius with the boldness he flaunts at the brothel for painted boys.

The takeover of the Morini fort marks three years since Skipio left home to fight. With their stronghold in flames, the last Morini flees to fight another day, while Rome sets camp a mile east of an estuary.

Soon after, construction on Gesoriacum begins. Days pass without foes, save a few women venting on the hillocks. They bare their backsides and break wind, amusing the Alpine-born, while those south of the Po show revulsion. Skipio’s tolerance is simple: no Alpine Roman can shake his family tree without a Gaul falling out.

Vitus, called Servius Tribune by the ranks, finds Skipio crouched near the mustering field. Restless aediles loiter in exercise tunics, idly swatting flies with swords. Publius Crassus sits tensely on his horse, gripping the reins, russet hair slicked by rain.

Vitus asks, “Why are we not practicing formations?”

“Decurion Servius says something’s not right,” Crassus tells him.

Titus Labenius, bald beneath his leather cap, draws beside them, his steed snorting. “Our enemy plans a sunrise attack,” he warns. “We must assign formations before nightfall.”

“I trust Servius the Younger,” says Crassus. “I’ll drill troops once he clears the field.”

Vitus winks at the frustrated Labenius, then strolls toward his son.

The meadow stretches toward a coastal hillock, where coarse grass grows thick from salt-soaked bedrock. Vitus moves quietly behind Skipio, observes his posture, and studies the field to spot what’s caught his son’s eye.

“Watching the weeds grow, Servius Decurion?”

Skipio remains crouched, eyes fixed on the field, absently turning a leafy twig between his fingers.

“See the lighter grass in straight patches?”

“An abandoned farm?”

“There would be uniform lines from years of plowing,” Skipio says. Like his father, he sees things from the inside out. “It’s as if the moles lived here and then left. But moles never leave.”

“What does that tell you?”

Skipio blinks. “The moles are Gauls.”

Crassus, an astute strategist, assigns Skipio the task of mapping the enemy tunnels. The Servian heir, however, offers a different approach, enlisting Planus and his engineers to uncover the first of many hollow corridors with their shovels. Most prove too narrow for a grown man.

A brave slave boy, enticed by the promise of roast duck, crawls into an exposed trough. When he surfaces several yards behind the battle camp, Skipio orders craftsmen to shape clay pipes. Planus and his men feed these pipes into the passage. Soon, smoke fills the pipes and floods the ducts; white wisps rise from the meadow. Spotting the smoke, Skipio suspects spies in the trees and orders archers to assemble. The archers fake a hasty drill and, at each halt, covertly seal the smoking air holes with wet mud.

Skipio orders those on the overnight watch to keep the pipe fires burning.

Dawn arrives quietly—sunrise brings no battle horn, only the slow stirring of smoke.

Suddenly, the night watchmen’s horn cuts through a wave of cries. Across the meadow, unarmed men in skins dig, while their women sob. Silence blankets the Roman ranks as Gallic men pull small bodies from the earth.

The obscene harvest cuts at Skipio’s heart.

“You didn’t put those babes in this battle,” says Vitus.

“I couldn’t fit inside, so Minerva sent me a child.”

“What does that tell you?” asks Vitus.

“We could’ve collapsed it instead. No need to choke them out.”

“If their goal were only to set fire to our munitions, there would not have been so many air holes.” Vitus grabs his son’s shoulder. “You didn’t put those babes in this battle. Now, dry your tears before the others see you.”